I’m trying something new for my class this first week of November. I’m going to reverse engineer the next Interdisciplinary Improvisation class that I teach for the Master of Digital Media Program—one that disassembles and analyzes the inner workings of what I’m going to teach in a reckless (and likely impossible) attempt to answer, “Why would you teach that?”.

Boring Stuff Already Said

I’ve already written about the why’s of improv in a digital media school or digital media environments—exercising:

- the embodiment of trust

- risk-taking

- culture building

- listening

- being receptive to what others offer

- building on other people’s ideas

… and many more valued competencies. Why those particular collaborative oriented competencies? Think of the improv course as one designed and persistently refined to in part ‘solve’ identified problems that learners may/will face when tasked to work together and deliver client-driven digital media artefacts.

Inception Moment (Level 1)

One of the biggest problems learners have is understanding the steps they need to take in solving ill-structured problems.These are the kinds of problems that are not easy to identify, that are multi-layered—that cannot be solved until attempts at solving them are balanced by equal attempts to fail at solving them. They tend to include the following:

- Defining the problem

- Generating possible solutions to the problem

- Evaluating alternative solutions

- Implementing the most viable solution

- Monitoring the implementation of that solution

- Repeating the process (Jonassen, 1997)

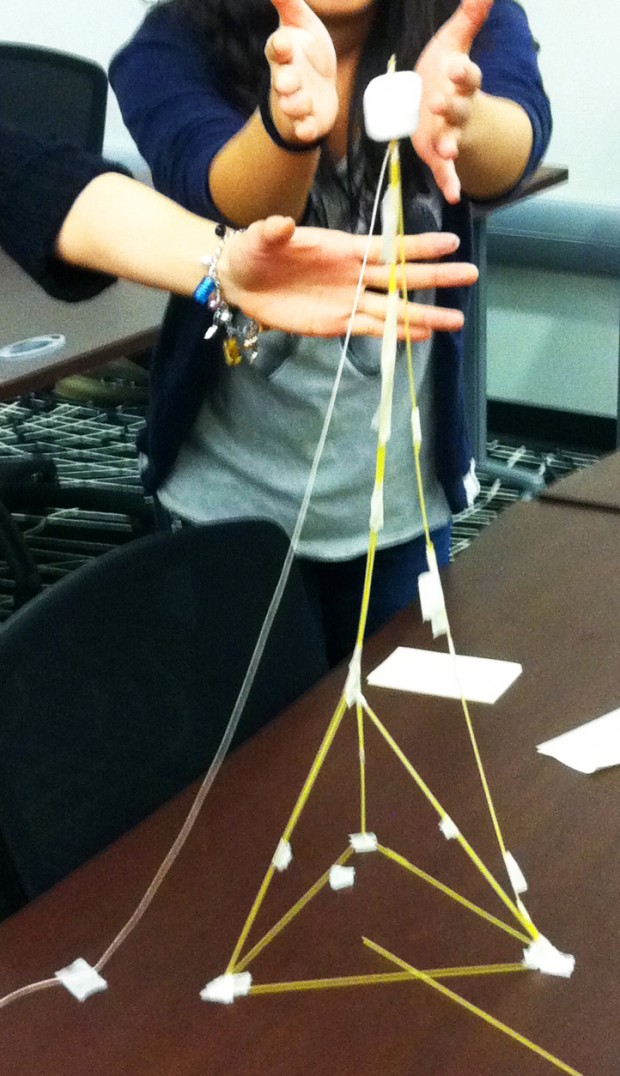

The Marshmallow Challenge is a great example of trying to solve a problem. Another way to emphasize the message of the challenge is to allow a group to do it more than once. Now many of you are likely reading this thinking ‘yes, yes…iterate, build-it, prototype’, and you’re right, and we do, particularly with our Projects 1 course handily facilitated by my colleague Larry Bafia.

Inception Moment (Level 2)

So what is the problem my next improv class will try to ‘solve’? Years ago, learners in our second and third cohorts often asserted the need for the Master of Digital Media Program to support “learner ownership of the problem solving process”. It is, in fact, one of the most important, challenging and rewarding competencies that learners can develop, and iterative attempts at facilitating an environment of practicing those problem-solving muscles occur regularly in all our courses. Herein lies the puzzler. How can learners emerge from our first semester relatively unscathed and leap forth ready to ‘own’ the problem solving process on our projects?

For those of you heuristically inclined (which is everybody), one possible answer is to create an opportunity for individuals and teams to become increasingly conscious of those tools and/or processes and/or rules of thumb that help them solve problems more efficiently.

Reclaiming Improv

So why exercise problem solving in an improv class?

Many people associate the word ‘improv’ with improv comedy. And although that’s partly true, each time I teach improvisation I need to reclaim the word. This isn’t necessarily because I have a background as a piano improviser, nor that improvisation is common to all artistic processes. It’s because improvisation is a mechanic that permeates all human activities, including problem solving in digital media.

The Improvisational in Problem Solving

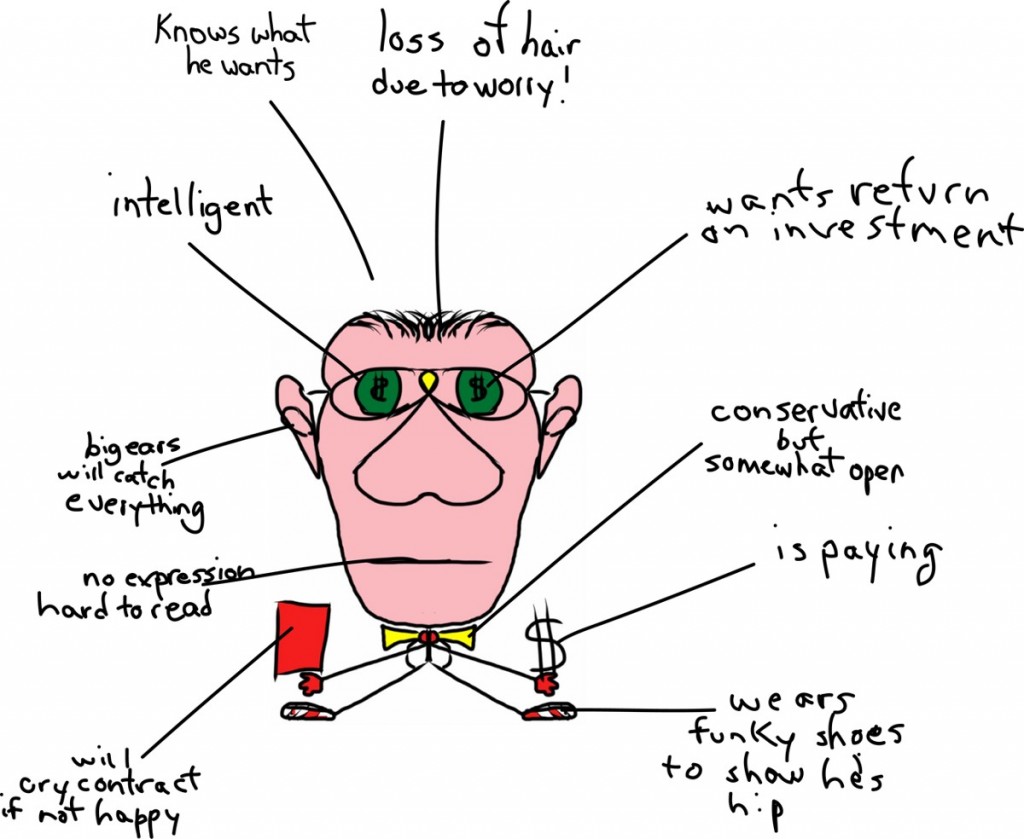

Now, although we all rely on heuristics when we solve problems, each design problem that we face at the MDM Program (and beyond) and the project that propagates it, has it’s own unique challenges. In our projects, teams of learners who may or may not have worked together need to align on a common process to manage a digital media project and work with a client they have likely never met before who has an emerging design idea for a digital artifact or prototype, and who is also dependent and reliant on the team to develop it. Like it or not problems will surface. Typically, these problems can be categorized as:

- Individual (buy-in)

- Collaborative (team, culture)

- Management (time, communication, scope)

- Project (ideas, content)

Sometimes the problems are simple but most of the time they are layered, like properly scoping a project you’ve never ‘built’ anything like before over the course of 12 weeks, so that a client can be assured that you will be delivering some kind of working prototype.

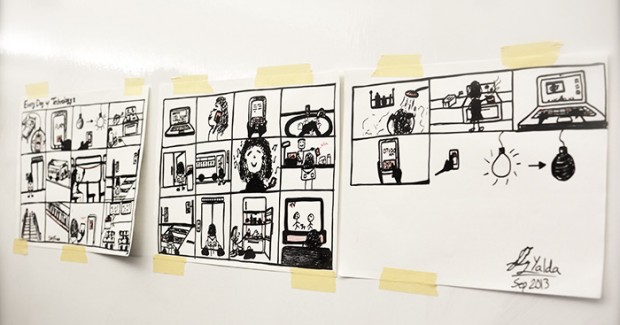

Or, realizing after 3 weeks that as a team you didn’t really identify the real problem or core need but the only way to find that out was by building a series of prototypes that the client realized, didn’t really match what it is they imagined.

The Heuristic Toolbox

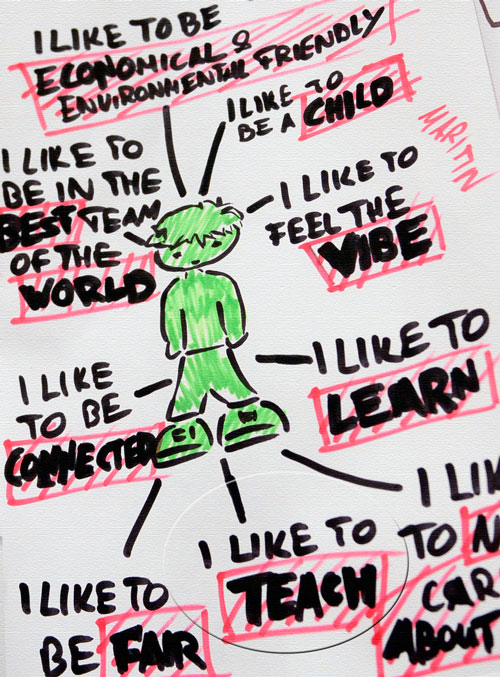

Each of us has different approaches to solving ill-structured problems. We each rely on previously applied problem-solving processes, and some of us have cultivated a certain level of expertise informed by our experience in our particular knowledge domain(s). In the case of learners at the MDM Program, they have the additional joy and pain of leveraging a series of user-centred design oriented tools from different design traditions, collaborative tools to address, resolve and avoid some team conflicts, tools to estimate tasks and prioritize features and tools to maintain persistent alignment throughout a project pipeline.

By the end of the next improv class then, learners will be able to leave the class with the beginnings (or continuings) of their own problem-solving process map—one that is malleable and ever changing. And importantly, they will embody the practice of drawing from this exquisite corpse of heuristics that they can eventually apply to solving problems in our Projects 2 course. That practice, a spontaneous, sometimes adhoc one, smothered in risk, where you never really know what new insights will emerge that will lead you to the discovery of an unexpected solution, maybe even… an innovation—an improvised process that once upon a time provoked one client to exclaim in a burst of cautious excitement— “You identified a problem we didn’t even think we had!!!”